|

|

|

and Beyond the Clouds

|

|

By John Demetry

In 1995's Beyond the Clouds, now available on DVD and video, John Malkovich plays The Director, who sums up Antonioni's aesthetic legacy in the opening voice-over: "I'm not a philosopher; on the contrary, I'm someone who's profoundly attached to images. I try to find what's behind them." He takes pictures of potential locations for his next films. The images he discovers/creates spark in his imagination the mini-narratives about morality and sensuality through which Antonioni flies Beyond the Clouds. There couldn't be a better time for these two works to be available to the public. With the dawning transition from film stock to digital video, the fate of the artform rests on audience standards of beauty, history, philosophy, and wonderment--aesthetics. These very concepts provide the dramatic fire for these Antonioni releases. The popular and critical success of films like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Gladiator, and Traffic pave the way for a visually illiterate and undiscriminating audience lost in a digital dark age. That's part of why The Mystery of Oberwald is so enthrallingly pertinent. Despite being shot on what now seems like archaic video (every zoom and tilt creeks like an early HBO soft-core porn show), Antoinioni's made-for-Italian-television movie is probably the most significant video-produced dramatic work I've ever seen--a hope for a brighter digital future.

The melodramatic function is rather blunt, though visually stunning and poetic--improving upon the script of the play. Antonioni adapts Jean Cocteu's tale of political intrigues overcome by tragic love, sustaining the play's captivating theatricality while stylistically penetrating the filmic and painterly impulse to capture reality, the interplay of light and perception, and the fleeting terrain of emotional and spiritual experience.

In one image, we get all of the film's dialectics: stage and movies, painting and photography, video and film that dramatize the conflict between reality and romantic projection. That's how Antonioni raises The Mystery of Oberwald above its political and theatrical cliches and beyond the limits of the television medium. The many layers of Beyond the Clouds can also be dizzying for viewers, like the recent theatrical re-release of Persona, that modernist masterpiece by Ingmar Bergman. That dizzying quality is also what makes these works so enthralling. The release of these Antonioni works on video provides a tool for the pleasure of critical thinking.

Again, the reference to painting and film as quests to recreating reality are ever-present themes (as in Antonioni's more popular, yet less accomplished, Blow Up). However, by explicitly casting a double in Malkovich's Director, Antonioni ultimately discovers exactly what it is that is "behind" the images. It is, of course, himself--and thus his very own perspective comes under the film's moral scrutiny. Each image has the luminousity of critical thought. In both of these works, Antonioni's passion for images takes us beyond our world-weary perceptions. Whatever the medium, that's what art is all about. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

In the forthcoming Facets video release of Michelangelo Antonioni's 1980

The Mystery of Oberwald, The Queen played by Monica Vitti describes the

assassination of her husband ten years prior. Antonioni's video camera pans

down from her face to a vase of red flowers. The flowers' hue suddenly bleed

out, tinting the entire frame: "there was blood on my knees." Antonioni's

images move beyond the physical.

In the forthcoming Facets video release of Michelangelo Antonioni's 1980

The Mystery of Oberwald, The Queen played by Monica Vitti describes the

assassination of her husband ten years prior. Antonioni's video camera pans

down from her face to a vase of red flowers. The flowers' hue suddenly bleed

out, tinting the entire frame: "there was blood on my knees." Antonioni's

images move beyond the physical.

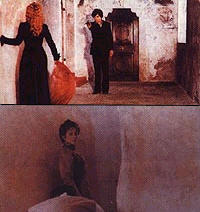

Scenes from The Mystery of Oberwald

Scenes from The Mystery of Oberwald  Antonioni's heady technique: There's a dissolve from a landscape painting by

one of the characters to the Cezanne that inspired it that hangs in a hotel

where Malkovich is staying. Malkovich examines that Cezanne, then a Cezanne

portrait. He copies the posture of the painting's subject. Then, Malkovich

mimics Antionioni's infamously intense, deliberate stare and concentration

when he sees Vincent (Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train) Perez leave

the hotel lobby and chase after a girl. Thus begins the final imagined

narrative within the larger narrative.

Antonioni's heady technique: There's a dissolve from a landscape painting by

one of the characters to the Cezanne that inspired it that hangs in a hotel

where Malkovich is staying. Malkovich examines that Cezanne, then a Cezanne

portrait. He copies the posture of the painting's subject. Then, Malkovich

mimics Antionioni's infamously intense, deliberate stare and concentration

when he sees Vincent (Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train) Perez leave

the hotel lobby and chase after a girl. Thus begins the final imagined

narrative within the larger narrative.