|

|

|

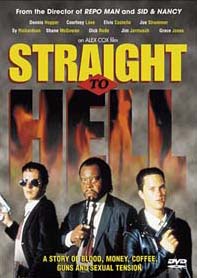

Three Alex Cox DVDs:

|

|

By John Demetry

The man who made "Walker" in 1987 has been permanently marginalized to the fringes after the earlier successes of Repo Man and Sid & Nancy. Perhaps his greatest film, Walker details the irrefutable legacy of U.S. imperialism from Vanderbilt to Reagan (and beyond), drawing the ire of film reviewers (Ebert's 0-star review of the film marked a permanent rut for him and for the culture). Perhaps his first two films could be accepted because they deal, in part, with pet liberal themes: anti-nuclear war and anti-drugs. However, Cox's films are always on top of and ahead of the times or of any such faddish politics. As his fascinating website, http://id.mind.net/~extang/acGeneral.html, exemplifies, Cox is deeply interested in and knowledgeable about politics, particularly tracking and attacking the continuing U.S. imperialism in Central and South America. With the Borges adaptation Death and the Compass, Cox's post-modernism explodes the power structure's manipulation of information into an official history. He finds parallels between our police state and the resulting gap of rich and poor in our country with the horror of South America's U.S.-sponsored Orwellian capitalist dictatorships. Years early, Cox anticipates Grace Lee Boggs' criticism of Al Gore's performance at the Coronation of George II published in the latest issue of the indispensable First of the Month: "You don't just strongly disagree with a right-wing coup or junta. You expose it as illegal, immoral and illegitimate, and you start building a movement to challenge and change the system that brought it on." For such a movement to exist, the films of Cox must play a role in challenging and sharpening the radical imagination. If it all sounds too polemical, too dry, remember that the imagination craves pleasure and beauty. Cox, and all great artists, discover revelatory ways of expressing those virtues. The wonderment of a Cox film is the openness, the expanse of his imagination. Note his dialogue with the Tod Davies, the producer/screenwriter of Three Businessmen, in the DVD's commentary track: "There's a little clue in here as to something else that's going on. Because what I'm doing in that conversation we just had is describing the plot of 2001." "When Alex was giving me his director's instructions about how to write the script, he said that the film he wanted to make was a low-budget 2001, by which he meant, I believe, that he wanted it to be about two guys who have the most amazing things happening around them but who couldn't access it and so would talk in the blandest and most banal terms through the whole thing."

Straight to Hell is a post-modern jamboree, a bring-your-own-brains party. that's why some fallaciously consider it shallow and self-indulgent - but such critics only expose their own shallow self-indulgence when they hail the tricked up, meaningless narrative shenanigans of Pulp Fiction. (Let's get my stance on Tarantino clear. If Tarantino used narrative to explore his own race-sex pathologies, then he'd be an artist. Instead, he uses narrative to disguise them. That lack of imagination is insipid.) Even the cover art for the DVD of Straight to Hell looks like a knock-off of "Pulp Fiction", probably as payback for how Tarantino's film ripped off Straight to Hell and Repo Man. It cues consumers to now see Pulp Fiction and its acclaim as an intentional reactionary step backward from the radical leap in appreciation of film tropes and post-modern existentialism that distinguished and damned Straight to Hell. Alert audiences bask in how Cox populates his Spaghetti Western heist film with a multi-culti cast, freed from the faux continuity of time and place demanded by Hollywood convention. Cox connects the way American capitalist greed secretly drives the mechanics of the plot with his investigation of how Spaghetti Westerns represented an international fascination with - and indoctrination by - the Hollywood/American mythology. That's why the humor of Straight to Hell, as Pauline Kael described Brian De Palma's era-defining The Fury, "shatters any Pollyanna thoughts - any expectations that a person's goodness will protect them." Cox's satire also takes up the running gag in Godard's Weekend about the automobile as totem of bourgie materialism. Here, the phrase "What's wrong with this car?" becomes an existential mantra.

The spatially complex framing of the Cinemascope shots is ideologically -

and visually - beautiful. Depth of field reveals slowly encroaching oilrigs

within the desert landscape that surrounds the film's Spaghetti Western

town. A mysteriously powerful shot reveals a Last Supper tableaux of the

cast joining in a spontaneous rendition of the song "Danny Boy."

The spatially complex framing of the Cinemascope shots is ideologically -

and visually - beautiful. Depth of field reveals slowly encroaching oilrigs

within the desert landscape that surrounds the film's Spaghetti Western

town. A mysteriously powerful shot reveals a Last Supper tableaux of the

cast joining in a spontaneous rendition of the song "Danny Boy."

Cox glories in his actors with the richness of his lighting that corrects conventional muddling of diverse skin tones and with the freedom of his burgeoning comfort with a mobile camera. This marks a genesis in Cox's style, leading to his signature long takes that provide a politically trenchant Kafkaesque neo-realism in Highway Patrolman (making the documentary realism of Traffic unacceptable) and a metaphysical formal pleasure in the plan de sequence/jump-cut alternations in The Winner (tackling trendy Tarantino triteness). As the parting of curtains prepares us, Cox investigates and indicts how Hollywood movies dictate popular perception and understanding of the world. (That's what the similar opening of Moulin Rouge prepared us to accept!) Cox and Davies explain a moment in Three Businessmen that exemplifies this intention: "The train has changed color. But the dialectic of watching a film, to use the Marxist terminology, you'd be surprised how many people can watch the film and not notice that the train has changed color."

Positions of power and privilege are undercut with each of Cox's narrative layers. The "present" setting of the story deals with a corrupt police commissioner deflecting blame for the mysterious fate of celebrity police detective Boyle. The flashback reveals the events that lead up to his disappearance, even as the commissioner's speculations become increasingly divorced from what we see. Within that flashback are both more flashbacks that offer clues to the motivations behind the sinister plot as well as manipulated media narratives (news reports, newspapers, interviews, press conferences, and political propaganda). Cox executes each of these layers in a distinctive style which, unlike the obvious use of tinting in Traffic that delineates location while pre-supposing objectivity, scrutinize the process of spectatorship. He encourages active imaginative film viewing. Once again, critics failed to elucidate meaning from style. Despite the fact that police brutality is a running motif in both the background and the foreground (it's even the key to the mystery!), Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times claimed that the topic was sacrificed to the film's flashy style and narrative ingenuity. The special visual effects, comic book colors, elaborate mise-en-scene and camera movements - this may be Cox's most visually stunning and elaborate film - all free our imaginations from the narrative oppression that serves to divorce film and art from political reality. That's the covert agenda of movies that portray cops as the good guys (such as Traffic or Die Hard). Cox doesn't allow that kind of safe distance from his films, as Davies explains: "Because when you look at a piece of art, you're alienated from the subject matter because you look at it and you say, 'That's a piece of art. I don't have to feel touched by it. I'm having a cultural experience.' That's the problem. When you watch a movie you're not actually asking, 'Is this possible? Why is this happening? What is going on here?' You're not asking that because the way that we're taught to watch a movie is that it's telling us what's happening. Whatever it tells us is happening is what we believe is happening. What these characters should be asking is: 'What is happening to us? Where are we? Who are we?' But they're not going to ask that. It's too frightening."

Cox connects the process of watching a movie with our relationship to political phenomena. The film's ostentatious spatial incongruity clarifies how economic globalization and film, as an ideological tool, infects our consciousness of the world. For example, the characters constantly speak as if the dialogue was taken directly from advertisements - call it Waiting for Godard. When Bennie performs a red-lit reverie on the benefits of his Plutonium Card, a very funny continuing joke begins. However, by the time Cox's camera reveals an answering machine next to an ashtray in an empty room in LA, the joke reaches a level of genuine existential terror. The source of that terror is the post-modern confusion of signs and meaning. The signification of a film cut in a Hollywood movie suggests spatial, temporal, or narrative continuity - but here it disrupts such continuity. The characters don't question it, but audiences must. Like Luis Bunuel, whose film The Exterminating Angel provides the name for Cox's production company, Cox recontextualizes Christian iconography throughout the film to subvert the power structures behind narrative manipulations and to illustrate the search for meaning. However, his take on spirituality is not just a joke - but a profound joke. He identifies the way our post-modern existence takes a metaphysical toll. In all of his films, Cox's satirical play with film tropes and pop forms frees the imagination from Hollywood's claim. Then his films teach us to apply that imagination to the real political world, to make connections beyond ourselves. The final twist of Three Businessmen gives you a transcendent giggle. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

Filmmaker Alex Cox, who has directed cult classics like Sid & Nancy and The Repo Man

Filmmaker Alex Cox, who has directed cult classics like Sid & Nancy and The Repo Man  Cox's mind illuminates with the brilliance of a Jean-Luc Godard, constantly

scanning the cultural landscape. There's that example in the Bunuelian

& Three Businessmen, and there's the sci-fi noir baroque style of Death and

the Compass (complete with Eighties-synth score).

Cox's mind illuminates with the brilliance of a Jean-Luc Godard, constantly

scanning the cultural landscape. There's that example in the Bunuelian

& Three Businessmen, and there's the sci-fi noir baroque style of Death and

the Compass (complete with Eighties-synth score).

Though some spectators resist, it's hard not to ask these questions while

watching Three Businessmen. We follow two businessmen's quest for a meal

in Liverpool that takes us, at the end of a train or cab ride, to Hong Kong,

Tokyo, and the desert.

Though some spectators resist, it's hard not to ask these questions while

watching Three Businessmen. We follow two businessmen's quest for a meal

in Liverpool that takes us, at the end of a train or cab ride, to Hong Kong,

Tokyo, and the desert.