|

|

|

By Jesse Monteagudo

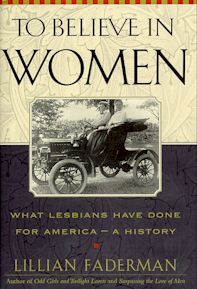

In To Believe in Women, award-winning historian Lillian Faderman relates how "lesbian domesticity" gave two generations of women the freedom to pursue higher education, enter the professions, undertake social work and improve the lives of all women. Unlike their foremothers, who had to marry out of economic necessity or societal pressure, these women had the freedom to form "Boston marriages" or "Wellesley marriages" (named after Wellesley College, where such arrangements were common among the student body and faculty).

Faderman gives us several reasons why women who lived with other women were more likely to be involved in careers and reform movements than women who were married or otherwise attached to men. First, "same-sex living arrangements permitted [women] far more time for social causes and other pursuits than was available to those who were busy running a multiperson household before the day of modern conveniences and with raising a family before effective birth control could limit the number of pregnancies." Second, "women in relationships that we would describe today as lesbian truly had a unique interest in the advancement of women and a psychological advantage in effecting that advancement: they were fighting for their lives, or at least for the quality of their lives." Finally, "Women who knew they were not going to marry also had less fear of offending men than a woman whose burning ambition was to be a wife. They could afford to be more militant and more devoted to pioneering pursuits in the cause of women, since they did not have to care what men thought." Fortunately, the idea of two "spinsters" living together was more socially acceptable at a time when most people thought women did not have a sexuality independent of men. Only after World War I, and the rise of sexology and psychoanalysis, were women-lovin' women branded as "sick" and "perverted" lesbians. In To Believe in Women, Faderman tells us how the love of women inspired many women to accomplish the near-impossible. Jane Addams' work at Hull House, and M. Carey Thomas's work at Bryn Mawr College, was only possible because of the support and nurturing they received from their long-time companions. What would the suffrage movement be without such "magnificent spinsters" as Susan B. Anthony or Anna Howard Shaw, or the women who loved them? The "never-married" Anthony treated her liaisons with other women as a form of marriage; while Shaw, Anthony's successor and "the strongest force for the advancement of women that the age has known" enjoyed a long-term, loving relationship with Anthony's niece, Lucy. Even the twice-married Carrie Chapman Catt, who carried the work of Anthony and Shaw to its final victory in 1920, considered her partner Molly Hay to be "the major person in her life". When American women finally got the vote, they owed their triumph to the likes of Anthony, Shaw, Catt, Mary Grew, Frances Willard and Alice Blackwell--all women who loved other women.

Progress is not inevitable. As Faderman reminds us in To Believe In

Women, the gains won by the likes of Jane Addams and Susan B. Anthony were

partially erased by the anti-feminist reaction that followed World War I.

Before that war, most women's colleges were led by women who, like Carey

Thomas, were in long-term relationships with other women.

Progress is not inevitable. As Faderman reminds us in To Believe In

Women, the gains won by the likes of Jane Addams and Susan B. Anthony were

partially erased by the anti-feminist reaction that followed World War I.

Before that war, most women's colleges were led by women who, like Carey

Thomas, were in long-term relationships with other women.

By the end of World War II the administration of most women's colleges were in the hands of men, and female students were encouraged to seek a worthy marriage instead of a fulfilling career. The distinguished Dr. Martha May Eliot, chief of the United States Children's Bureau, was branded an "unnatural female celibate" by a U.S. Senator (male, of course); while prison reformer Miriam Van Waters had to retreat into the closet after the Hearst press conducted a witch hunt against her. Only after 1960, and the second wave of feminism, would a new generation of women again choose a lesbian life over a conventional marriage. Faderman herself belongs to that generation. To Believe In Women is a worthy successor to Lillian Faderman's previous, award-winning histories, Surpassing the Love of Men and Odd Girlsand Twilight Lovers. All three histories are important contributions to lesbian studies, as they uncover the lesbian past and the women who lived it. As Faderman writes, "Such a preservation of lesbian history is important, not simply to set the record straight (or, in this case, unstraight) but also to provide for those lesbians who hunger for what Van Wyck Brooks has called (in another context) a 'usable past.'" You don't have to be a lesbian to learn from the lives and achievements of a group of amazing women, who did so much because they "believed in women". To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America-A History by Lillian Faderman; Houghton Mifflin; 434 pages; $30.00. |

© 1997-99 BEI

Gertrude Stein & Alice B. Toklas, 1908: Two women who helped shape the 20th Century

Gertrude Stein & Alice B. Toklas, 1908: Two women who helped shape the 20th Century