|

|

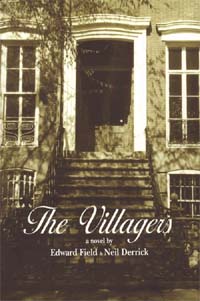

A Novel of Greenwich Village Courtesy of One Institute Press The Villagers: A Novel of Greenwich Village by Neil Derrick and Edward Field, Painted Leaf Press, 1999 617 pages, (Amazon price: $16.06)

This immensely readable book is a panoramic treatment of four generations of an American family, the Endicotts, most of whom live, successively, in a house on the actual Perry Street in Greenwich Village (an area in which Derrick and Field themselves have lived since 1960). Covering the period from 1845 to 1975, it is replete with well-researched American social and literary history, the few anachronisms in the latter probably detectable only by a professor of American literature. Against the background of the Civil War, World War I, Lindbergh's flight, the Sacco-Vanzetti execution, the stock-market crash, the Spanish Civil War, Pearl Harbor, World War II, McCarthyism, the Endicotts marry or interact with Irish, Italians, Jews, and blacks, all of whom exhibit the prejudices and experience the problems that abound in the American melting-pot of which the Village is a microcosm, though more liberal and liberated than other parts of the country, especially between 1909 and 1929. The historical event which has the most direct impact on the family is the construction of the subway system in New York City, envisioned and built by its dominant member, Patrick Endicott, the illegitimate son of the patriarch Tom Endicott and his earthy Irish mistress Molly Hanlon. (The reconciliation scene between father and son is one of the book's highlights.) What happens to Tom, Molly, his invalid wife, Fanny, their children, Claude and Veronica, the crude engineering genius, Patrick, his intellectul wife, Elizabeth, their children, Alice, Polly (the product of the neglected Elizabeth's extra-marital escapade but the unknowing Patrick's favorite), and the youngest, Eugene, and Alice's son, Dominick, her grandson, Frank, and Eugene's, son Seth is the stuff of the novel. Adding verisimilitude to the story, various Endicotts encounter real-life figures such as Walt Whitman, Henry James, Jim Brady, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Mabel Dodge, John Reed, John Sloan, and Edna St. Vincent Millay. In a deliciously comic scene, for example, Henry James is invited to the Endicott home for dinner for the literary benefit of Veronica, an aspiring poet, but James has eyes and ears only for the virile, good-looking Patrick, who monopolizes the conversation with his talk about subways, much to the chagrin of Veronica and her mother--a sly reference to James's homosexuality. In the first half of the book, apart from this scene and one in which there is a lesbian approach to Elizabeth by her friend, a black singer, there is little dealing with gays. But the second half livens up, in this respect, when for a considerable stretch the adventures of Eugene, the late-coming-out writer, who forms a touching liaison with the much-younger Portuguese fisherman Manny Silva, take center stage. The relationship between them is discreetly--almost too discreetly--described; one would welcome more psychological detail and a larger role for the bisexual Silva, the most likeable character in the novel. It is perhaps inevitable--but nevertheless disappointing to gays--that he eventually marries instead of finding another male lover after Eugene's death. The characters are varied and well differentiated and dovetail effectively with each other in an absorbing, wide-ranging plot. Most attention is paid, in the second half of the book, to Polly, the last Endicott to inhabit the house. Her ownership of an art gallery and her artist friends allow the authors to include, unobtrusively, an account of American painting and the art world during the two decades beginning in the early 1950's, apparently one of their major interests then. (Derrick once worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and he and Field knew and know many artists.) Several of the non-family characters are especially memorable, particularly the wise, lusty Corinne; her wild Hungarian lover Zoran; and the opportunistic go-getter Hymie Liebman, Polly's lover-turned-friend, who buys the house and saves it from destruction (it is a a good real-estate investment for him) and Polly from poverty. The structure of the novel is linear, straightforward, uncomplicated. The style is serviceable, inconspicuous, less poetic than one might expect from Field, who never attempted prose before this collaboration with Derrick, whom his eyes serve well. Whoever copy-read the book did an excellent job; I noticed no typos and the only stylistic infelicity I observed were the repetitious descriptions of Norma as "the dancer" on pages 533, 535, and 540. If the future work of Derrick and Field is as successful as The Villagers, readers are in for a treat. And if the two tackle the gay theme even more boldly and intensively, gay readers should flock to buy their books. Arnold T. Schwab, a Harvard Ph.D., has taught English at UCLA, the University of Michigan, and, for twenty years, at California State University, Long Beach. A scholar, biographer, and poet, he has published four scholarly books including a prize-winning biography of the important late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century critic James G. Huneker and many articles and reviews on American literature, music, and drama. His book of poems Elegy for a Gay Giraffe appeared in 1988, and his poems have been printed in California Voice, Gay Books Bulletin, and other magazines and newspapers. Now retired, he lives in Westminster, California. |

Neil Derrick and Edward Field have written a three-decker novel that is anything but Victorian except in length and scope. Derrick, a veteran novelist who lost his sight in 1972 after an operation for a brain tumor, and his longtime partner Field, to my mind with James Merrill the best American poet writing on gay themes in the last forty years, published an earlier version of The Villagers in 1982 but revised, expanded, and republished it in 1999.

Neil Derrick and Edward Field have written a three-decker novel that is anything but Victorian except in length and scope. Derrick, a veteran novelist who lost his sight in 1972 after an operation for a brain tumor, and his longtime partner Field, to my mind with James Merrill the best American poet writing on gay themes in the last forty years, published an earlier version of The Villagers in 1982 but revised, expanded, and republished it in 1999.