|

|

20th Century Gay Publications Author, Leading the Parade On this auspicious beginning of Reno/Tahoe Outlook, I felt it appropriate to present what I consider the ten most significant 20th Century newspapers/magazines serving the gay community. 1. Friendship And Freedom (1925)

As Gerber expounded in ONE Magazine in 1962, "Friendship and Freedom would keep the homophile world in touch with the progress of our efforts. The publication was to refrain from advocating sexual acts and would serve merely as a forum for discussion." Gerber added, "I then set about putting out the first issue of Friendship And Freedom and worked hard on the second issue. It soon became apparent that my friends were illiterate and penniless. I had to both write and finance. Two issues, alas, were all we could publish." The Society for Human Rights abruptly terminated in 1925, as police arrested Gerber and three other members when one member's wife complained to authorities, and the magazine surfaced. Despite eventual acquittal, Gerber was left penniless and dispirited. No known copies of Friendship And Freedom exist. If one could be found, it would be incredibly historically significant as America's first known gay publication. 2. Vice Versa (1947-48)

She typed two meticulous originals (and multiple carbon copies) each month through February 1948. As Rodger Streitmatter noted in Unspeakable, "Vice Versa looked more like a term paper than a newspaper, and it made no pretense of attempting to answer who? what? when? or where? regarding the news of the day. Yet it set the agenda that has dominated lesbian and gay journalism for fifty years ." For a 1940s-produced magazine, it bore no hint of apology. Its issues included reviews, poetry, Letters to the Editor, original fiction, and commentaries. In 1993's Happy Endings, Lisa recalled, "When I turned out my first copy, I probably knew about four people. And the next month, they introduced me to some more, and I knew ten people. And eventually it grew to more girls than I had copies!" But publication ceased when Howard Hughes bought RKO in 1948, as the studio terminated Lisa's employment. As she told me in 1994, she "had to quit because there was no opportunity to type privately or anything [at succeeding jobs]. So that's why Vice Versa bit the dust." (She also told Streitmatter, "I was getting a little social life, too - becoming a sly little minx. I was discovering what the lesbian lifestyle was all about, and I wanted to live it rather than write about it.") "Lisa Ben" remains alive and well with her eleven cats in her little house in Burbank, California. She remains one of the movement's little-known pioneers. 3. ONE Magazine (1953-1969)

The precursor organization of the modern American gay movement was Mattachine, conceived by Harry Hay in 1948 and founded with four other men in 1950. Its members wished to bring hope and comfort to homosexuals downtrodden by a hostile society. But how?

The precursor organization of the modern American gay movement was Mattachine, conceived by Harry Hay in 1948 and founded with four other men in 1950. Its members wished to bring hope and comfort to homosexuals downtrodden by a hostile society. But how?

On October 15, 1952, during a Mattachine discussion group meeting, its host suggested that the assemblage create a monthly magazine to disseminate information about homosexuality. While the host resigned the next day, his chance remark spurred several in attendance to create ONE Magazine (its name taken from a Thomas Carlyle quote, "A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one"). The magazine soon birthed its own organization, ONE, Inc. (Mattachine would create its own publication, Mattachine Review, in 1955.) ONE's first issue was published (from one member's sister's basement!) in January 1953. In Unspeakable, ONE's Circulation Manager Don Slater remarked, "Before this time, homosexuals just talked - whispered, really - to each other, [which] can't create a social movement, a mass movement. For the first time, ONE gave a voice to the 'love that dare not speak its name.' The magazine was the beginning of the movement."

4. The Ladder (1956-1973) A fledgling organization begun by four lesbian couples in San Francisco in 1955 failed to catch fire a year later, having increased to only 15 members. What to do? Well, why not start a newsletter? Born in October 1956, The Ladder was the brainchild of the Daughters of Bilitis's (DOB's) founders (and journalists) Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, who described DOB in 1972's Lesbian/Woman as "a women's organization to aid the Lesbian in discovering her potential and her place in society." The bold gamble paid off: One year later, DOB boasted 45 members and The Ladder 400 subscribers. In Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, gay historian John D'Emilio noted, "The Ladder offered American lesbians, for the first time in history, the opportunity to speak with their own voices." Phyllis edited The Ladder from its inception until 1960; Del followed through 1963.

Then a fresh wind blew into The Ladder in 1963, when Philadelphian Barbara Gittings assumed the editorship. Barbara steered The Ladder in a much more aggressive and confrontational direction, reflecting her exposure to the more radical ideas (such as picketing) of contemporary East Coast gay male leaders. (As future Ladder editor Barbara Grier told me, "From the beginning, [it] was primarily a lesbian magazine.

When Gittings took over, it became a gay magazine, with a little bit of mention of lesbianism.") In 1966, Martin and Lyon removed Gittings from the editorship, and resumed their duties.

Then a fresh wind blew into The Ladder in 1963, when Philadelphian Barbara Gittings assumed the editorship. Barbara steered The Ladder in a much more aggressive and confrontational direction, reflecting her exposure to the more radical ideas (such as picketing) of contemporary East Coast gay male leaders. (As future Ladder editor Barbara Grier told me, "From the beginning, [it] was primarily a lesbian magazine.

When Gittings took over, it became a gay magazine, with a little bit of mention of lesbianism.") In 1966, Martin and Lyon removed Gittings from the editorship, and resumed their duties.

The Ladder's last editor ascended in 1968 when Kansas City, Missouri's Barbara Grier, a regular contributor since the Fifties, claimed the position "by default. No one else would take the job." When Grier assumed the editorship, The Ladder had perhaps 300 paying subscribers; four years later, Grier counted 3,800. But in 1970, Grier and then-DOB President Rita Laporte "stole" the magazine from DOB, and published it independently from outside greater Sparks, Nevada. (See, we have a place in gay American history too!) Under Grier's reign, The Ladder metamorphosed again, arguably targeting women generally rather than lesbians specifically. Unfortunately, because "the only ads a magazine like The Ladder could get were the kinds of things that it would not have wanted," The Ladder folded in 1972. During its 16 years of publication, The Ladder's jumble of homophile news, poetry, fiction, history, biography, and personal narratives - as well as its sheer existence - positively impacted the lives of thousands of lesbians who discovered options other than lesbian bars and virtual isolation. As lesbian comic and women's festival producer Robin Tyler told me, "Reading one little article in '59 by Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon got to me and changed my life, from being a [potentially] suicidal kid in Canada, to being out of the closet immediately, never knowing what it was like to be in the closet." 5. drum (1964-1969) In retrospect, most of the pre-Stonewall gay publications were relatively assimilationist and tame. But drum was racy, raunchy - and brilliant. drum (subtitled "sex in perspective") began as the newsletter of Philadelphia's Janus Society. Clark Polak, a brash homophile leader in the mid-Sixties, appropriated editorship of the newsletter, and told Streitmatter he "began drum Magazine as a consistently articulate, well-edited, amusing and informative publication. I envisioned a sort of sophisticated, but down-to-earth, magazine for people who dug gay life and drum's view of the world." (Or, as John Loughery wrote in The Other Side of Silence, "drum's philosophy was plain enough: it was time to raise a little hell.") In addition, Polak was the first gay editor to hire a professional clipping service to obtain gay-related articles from around the country. Veteran gay journalist Jack Nichols additionally told me that "drum published nudes - frontal nudes - first, in any gay publication in America." But even Ladder editor Barbara Gittings reflected on drum's positive impact with me, noting that despite showing abundant male flesh, drum and similar magazines that followed "were a way of getting [movement activity] information to people who wouldn't bother to read it otherwise." drum even boasted the first gay comic strip (the risquι "Harry Chess: The Man from A.U.N.T.I.E."). Polak's formula proved enormously successful; by 1966, drum's 10,000 circulation surpassed that of all the then-extant homophile publications combined. However, that formula also left Polak vulnerable to police and legal intervention when the Buffalo, New York Postmaster seized drum's March 1966 issue. While ultimately distributed, Polak later proved less fortunate. drum abruptly ceased publication by May 1969, as Polak awaited a federal grand jury indictment for mailing allegedly obscene material. He evaded a prison sentence only by agreeing to cease publishing drum and to leave Philadelphia. Yet drum's movement contributions could not be denied, nor could its founder's aspirations be denigrated. New York pre-Stonewall activist Dick Leitsch recalled for me a heated discussion among movement leaders in the Sixties regarding "which one of them is the Martin Luther King of the gay movement. And they went on and on, just yelling and screaming . And so, Clark Polak just sat in a corner and I said, 'Hey, Clark, don't you want to be Martin Luther King too?' He said, 'No, I just want to be Hugh Hefner.'" Polak never quite reached that level of sophistication with drum, but not for lack of trying. 6. The Advocate (1967-Present)

It began its life humbly as the newsletter for a Los Angeles gay group, Personal Rights in Defense and Education (PRIDE). When the organization changed its focus, "Dick Michaels," his lover, and a business partner bought the newsletter from PRIDE for $1, and changed its name to the Los Angeles Advocate. In 1971 Michaels wrote, "the basic premise of The Advocate at its founding was to publish a newspaper that would have widespread support from all segments of the Gay Community; a newspaper that would be a strong voice through which all factions could speak; a newspaper that might unite all Gays in our common cause; a newspaper that might someday be a strong influence within the homosexual society and, perhaps, even outside it; a newspaper that might help homosexuals realize that they are important as human beings, that they should not be ashamed of their homosexuality, and that they have rights that no majority may take from them." Time would prove him right on almost all counts (few lesbians found themselves comfortable with its male-oriented focus). Despite the partners' minuscule $200 investment, the magazine tasted success almost immediately after its September 1967 appearance. (They initially kept costs low by copying the publication at the ABC television studio where Michaels's lover worked.) Despite incredible odds against its success, it reached a reported press run of nearly 40,000 by the end of 1970, the same year Michaels de-regionalized the publication, shortening its name simply to The Advocate. (Personals ads and photographs of "pretty boys" didn't hurt sales, either.) By 1974, it was unquestionably the most successful American gay magazine. And the man with the most power and money in the gay community wanted it. Entrepreneur David B. Goodstein bought The Advocate in 1974 for a cool $1 million (a handsome return on Michaels's investment only seven years earlier!). An even less likely candidate for journalistic success than Michaels, Goodstein (who described himself in The Advocate's pages that year as a "stubborn, angry, tough-minded pioneer son-of-a-bitch") possessed no journalistic background whatsoever. But the professionally-successful Goodstein had lost a high-profile banking job in 1971 because of his sexual orientation, and that experience drove him into the movement with a vengeance.

The Advocate's transformation from a news journal to a lifestyles magazine on Goodstein's watch did not sit well with many readers, and sales stagnated for several years. (Veteran gay journalist Jim Kepner told me, "The people he was aiming at weren't ready to pick up the paper for a long time. And the people who had been picking up the paper didn't like what it turned into very quickly.")

The Advocate's transformation from a news journal to a lifestyles magazine on Goodstein's watch did not sit well with many readers, and sales stagnated for several years. (Veteran gay journalist Jim Kepner told me, "The people he was aiming at weren't ready to pick up the paper for a long time. And the people who had been picking up the paper didn't like what it turned into very quickly.")

However, Goodstein's financial underpinning and his vision for a professionalized gay movement shaped The Advocate into the slick journal it remains to this day (despite periodic criticism regarding that slickness). After Goodstein's death in 1985, a series of editors helmed the journal, but none with his extraordinary influence. Virtually every gay male writer of note has written for The Advocate (even I had a Letter to the Editor published in 1985!), and it shaped the literary lives of several, including John Preston, Mark Thompson, and Randy Shilts. The Advocate served - and serves - as the most consistent voice of America's gay liberation/civil rights movement. 7. GAY (1969-1973)

Their first column began, "Lige and Jack are male lovers who dig life together and think it's a groove. [Note: People really talked that way in the Sixties!] They poke fun at those who would make love a crime, and hope for the day when homosexuals and heterosexuals are happily integrated." SCREW's circulation grew to 150,000, and Lige and Jack became among the first homosexuals to explain and de-mystify homosexuality to a mostly heterosexual readership. "The Homosexual Citizen" proved so successful that Goldstein and business partner Jim Buckley teamed with Nichols and Clarke to create GAY newspaper, which debuted on November 15, 1969. Within a month, GAY built a circulation of 25,000. Like The Advocate, GAY launched several writers' careers. Nichols reminisced with me regarding GAY in 1994:

After almost four years as a bi-weekly paper (weekly from April 1970 to October 1971), and second in American targeted gay community publications only to The Advocate, Nichols and Clarke tired of the routine after 110 provocative issues, and moved to Florida in July 1973. But it was great while it lasted! (Since our interview, Jack became one of my dearest friends.) 8. Gay Community News (1973-circa 1995)

Unspeakable reported that GCN "was committed to social change, and its editorial page spoke unremittingly from the Left." But GCN embraced a wide agenda: "Whether Bostonians took to the streets to protest apartheid, racism, or threats to a woman's right to have an abortion, GCN highlighted the event on the front page - each time including an estimate of how many gay people had joined the march." Additionally, GCN was "committed to raising the voices of lesbians to a decibel level fully equal to that of gay men." GCN also went where other publications wouldn't around AIDS issues in the early Eighties. Vaid described GCN to me in 1995 as "the one rag that every activist in the grass-roots read. It was a really amazing collection of people at Gay Community News. And they shaped my politics tremendously." But that doesn't mean being family at GCN was easy. As Nancy Walker, a GCN staffer from 1976 to 1984, told Marcus, "I would say at least 90 percent of the people at any one time at GCN were thoroughly radical . We didn't get along with each other at all, even people of the same political persuasions, but you could be yourself at GCN. GCN was a sanctuary. That's how I felt. It may not sound like it, but I just loved to be there." Even a devastating July 1982 fire that burned GCN's offices to the ground couldn't quench the message, or the messengers: Walker related that "[W]e just moved over to a place in Cambridge. We never missed a week ." By the end of the Eighties, GCN achieved a circulation of 60,000. But it closed its doors in 1992, when longtime contributor Michael Bronski admitted that "We managed to get on by hook or by crook, but hippy [sic] economics are no longer tenable." However, Vaid told me that she "got involved in December of '92 to try to get [GCN] out of debt, and restructure the whole organization. And we're doing it! We're publishing as a quarterly now." She also related that GCN's "alumni are some of the most amazing writers, thinkers, activists around. Some are dead, and many are still organizing. Almost all are still involved in the movement in some way." 9. Christopher Street (1976-1997) Of the post-1940s magazines mentioned here, Christopher Street probably emphasized "hard news" least. But if you wanted to drop in on a chat between its writers and prominent gays (usually other writers), or read an eloquent piece by a good gay author, it was the place to go. In the Introduction to 1983's Christopher Street Reader, Michael Denneny wrote that "Christopher Street has never tried to develop a party line; we always thought our task was to open a space, a forum, where the developing gay culture could manifest and experience itself." But Unspeakable reported that "Christopher Street sought to become a gay New Yorker. Because Christopher Street was aimed at sophisticated readers, it sought to distance itself from graphic sexual discussions or images. Publisher Charles Ortleb said, 'No one will ever masturbate over this magazine.'" (However, Ortleb understood the centrality of sex in his readers' lives, and addressed it "through the wry humor of cartoons similar to those that had become a trademark of the New Yorker. The Christopher Street versions were often mildly chastising of the gay fast lane, with some cartoons shaking their fingers at promiscuity and the brief duration of many gay relationships.") Ortleb also founded the New York Native in 1980 "as a gay Village Voice that would pander sufficiently to the gay male desire for smooth flesh and bulging sex organs to pull in the profits needed to supplement the literary magazine [Christopher Street] that Ortleb otherwise would have to abandon." But like most gay publications, Christopher Street fell prey to gender divisions. As Denneny wrote, it "started with a determined effort at gender parity, which lasted about a year and a half. [T]he magazine was, by and large, never able to win the loyalty of women readers, and the women on the staff slowly drifted away. At the time all this led to some muttered sound and muted fury and hurt feelings on both sides, but [t]he connection between gay men and gay women was only ideological; we did not really share a world in common." Christopher Street ceased publication in 1997. 10. OutWeek (1989-1991)

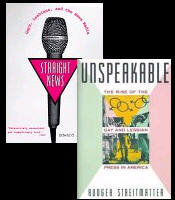

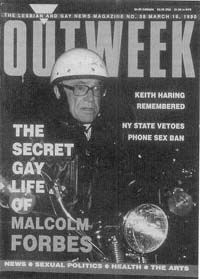

In 1989, successful phone-sex entrepreneur Kendall Morrison used the substantial profits from his ventures to found a lesbian/gay magazine, OutWeek. Gabriel Rotello, a New York party promoter, planned to edit the magazine, and soon met aspiring gay journalist Michelangelo Signorile, an angry young man annoyed at the hypocrisy of gays who remained closeted to maintain their position and prestige. As Edward Alwood wrote in Straight News, "The brash and irreverent new magazine was written in an inflammatory style. It reflected the deep anger and rage that fueled ACT UP." It criticized gay and straight society with abandon, but saved its harshest venom for closeted gays. Alwood continues, "In August 1989 Signorile created a second column for OutWeek, Peek-A-Boo, which listed the names of more than sixty closeted celebrities . Although there was no explicit explanation for why the names appeared on the list, the message to closeted gay celebrities was clear." In response to his article outing gay magazine publisher Malcolm Forbes following his death in 1990, Signorile remarked in New York's Village Voice, "The message to rich and famous queers is: come out while you can, because when you die you'll be thrown on the cover of a magazine and labeled a closet case. I may even bring you out alive." In the meantime, Unspeakable reported that OutWeek's employees and freelancers "grew displeased with how poorly the magazine was managed . The management problems evolved from Morrison and Rotello coming to the magazine as activists rather than from business backgrounds."

"Although the publishers expressed hope that it would reopen, privately they concluded the magazine was dead. Its offices were padlocked on June 27, 1991." (Signorile's piece ultimately ran in the venerable Advocate, expanding the issue of outing and its impact throughout the gay and mainstream presses.) In Unspeakable, Streitmatter editorialized, "The vehicle for outing, the whirling dirvish [sic]OutWeek, [was] a victim of a clash between activists eager to support radicalism and businessmen more interested in larger profits - with the businessmen carrying the day." In retrospect, Rotello wrote in an April 1995 Advocate article, "Essentially the media have grudgingly accepted OutWeek's once-radical argument. Outing, once so contentious that it threatened to tear the community apart, is now so commonplace that it's hard to remember what the fuss was about." But that "fuss" changed both straight and gay journalism forever. Author's Note: Much of this information was gleaned from Edward Alwood's Straight News and Rodger Streitmatter's Unspeakable. My gratitude goes out to them for their pioneering work regarding the gay press. The Author's Forthcoming Book: Paul D. Cain's Leading the Parade, a book profiling several movers and shakers in American lesbian/gay history in the latter half of the 20th Century, is in Scarecrow Press's 2001-02 catalog, and should be published before the end of 2001. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

© 1997-2002 BEI

The author, Paul D. Cain, wishes to

express his indebtedness for this article to two scholarly sources:

Edward Alwood's Straight News and Rodger Streitmatter's Unspeakable

The author, Paul D. Cain, wishes to

express his indebtedness for this article to two scholarly sources:

Edward Alwood's Straight News and Rodger Streitmatter's Unspeakable  Lisa Ben, which is an anagram for "Lesbian", was the editor of Vice Versa. She is seen here at the 1998 memorial service for activist Jim Kepner in Los Angeles

Lisa Ben, which is an anagram for "Lesbian", was the editor of Vice Versa. She is seen here at the 1998 memorial service for activist Jim Kepner in Los Angeles  The grande dame of gay publishing, The Advocate also predates Stonewall. The vision of two men - one to create it, the other to expand it - shaped the magazine, and gay journalism, to this day.

The grande dame of gay publishing, The Advocate also predates Stonewall. The vision of two men - one to create it, the other to expand it - shaped the magazine, and gay journalism, to this day.

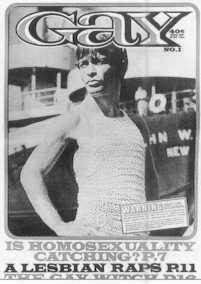

Lige Clarke on the cover of Gay

Lige Clarke on the cover of Gay Jack Nichols, Gay editor then, GayToday editor now

Jack Nichols, Gay editor then, GayToday editor now  Lesbian Author Urvashi Vaid was on the board of the Gay Community News

Lesbian Author Urvashi Vaid was on the board of the Gay Community News  As influential gay magazines go these days, its life was remarkably short, and its readers relatively few (never more than 30,000). But in just two years, OutWeek changed journalism with just one controversial word: "outing."

As influential gay magazines go these days, its life was remarkably short, and its readers relatively few (never more than 30,000). But in just two years, OutWeek changed journalism with just one controversial word: "outing."

Michelangelo Signorile, an outer at OutWeek

Michelangelo Signorile, an outer at OutWeek