Lucien Carr, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The death of writer Herbert Huncke in 1996, and of his colleagues William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg in 1997, ended one of the most influential literary movements in American history: the Beat Generation. Burroughs was the Beats’ father figure and literary innovator; Ginsberg its publicist and poet laureate; and Huncke the flamboyant figure who inspired the Beat writers and introduced the word “beat” to our vocabulary. Though several minor writers and personalities remained alive, to all extent and purposes the Beat Generation was dead.

To Huncke, who took the word from show business and carnival slang, “beat” meant “exhausted, at the bottom of the world, looking up or out, sleepless, wide-eyed, perceptive, rejected by society, on your own, streetwise.” Jack Kerouac took Huncke’s word and expanded on it in 1948 when, according to John Clellon Holmes, he referred to theirs as “a beat generation.” Holmes’s 1952 article, “This Is the Beat Generation,” used Kerouac’s creation and launched it upon an unsuspecting world. In 1957, after Kerouac’s On the Road became a bestseller, Herb Caen of the San Francisco Chronicle coined the term “beatnik” to refer to the unorthodox youngsters who gathered in the bars and coffee houses of San Francisco’s North Beach.

A section devoted to the beat generation at a bookstore in Stockholm, Sweden.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Kazin called the Beat Generation “a family of friends,” a term not unknown to most LGBT people. It was also a “community of outlaws,” one united by their members’ taste for unorthodox (and illegal) sexuality and drug use. It began in New York City in 1944, when the newly acquainted Burroughs, Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Lucien Carr began their quest for a “New Vision” in literature. It flourished through the influence of enigmatic figures like Huncke and Neal Cassady, who arrived in New York in 1946 to become Kerouac’s friend and Ginsberg’s lover. And it became a nationwide movement in the 1950’s, when it joined forces with the poets of the so-called “San Francisco Renaissance”: Kenneth Rexroth, Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, Lew Welch and others. It was a San Francisco poet, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who published and popularized the Beat writers via his City Lights Books and City Lights Bookstore.

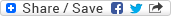

1944 Denver mugshot of Neal Cassady

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Burroughs was the Beat Generation’s most innovative writer. The scion of a wealthy family – his grandfather invented the Burroughs adding machine – Burroughs was born in 1914, a decade before his Beat contemporaries. Burroughs personal life can be summarized by the titles of two of his novels, Junky and Queer. Burroughs was arrested for heroin and marijuana possession in 1949 and fled to Mexico with his wife, Joan. There, Burroughs caused a bigger sensation when he accidentally killed Joan (1951) in a drunken game of William Tell. Burroughs spent much of the fifties and sixties in Europe and North Africa, where he wrote a series of classic and controversial books, including Naked Lunch (1959), which was tried for obscenity in Boston.

Burroughs was as original in his thinking as in his writing. He was a thorough libertarian, who opposed gun control as well as laws against drug use and sexual practices. Burroughs, said Ginsberg, “is one of the very few gay liberation minds who is thinking in ultimate philosophical terms about sexuality, about the nature of ‘apparent sensory phenomena’ …. He’s one of the few that has actually questioned sex at the root — not merely rebelled from heterosexual conditioning or heterosexual, social/moral fixed formations – to explore love between men as he has experienced it.”

Irwin Allen Ginsberg, wrote Steven Watson in The Birth of the Beat Generation, was “one of poetry’s frankest celebrators of homosexuality.” Born in 1926, Ginsberg went to Columbia University in 1943, where he met and loved Kerouac and Cassady. A series of legal and personal problems landed Ginsberg at the Columbia Presbyterian Psychiatric Institute (1949-50). It wasn’t until 1954, after he moved to San Francisco and met his longtime partner Peter Orlovsky, that Ginsberg learned to accept himself, thanks to the efforts of a friendly psychiatrist:

“I was being psychoanalyzed at Langley Porter Clinic, an elite extension of U.C. Berkeley Medical School. He was a very good doctor, and I said: ‘You know, I’m very hesitant to get into a deep thing with Peter, because where can it ever lead. Maybe I’ll grow old and then Peter probably won’t love me – just a transient relationship. Besides, shouldn’t I be heterosexual?’ He said, ‘Why don’t you just do what you want. What would you like to do?’ And I answered, ‘Well, I really would just love to get an apartment on Montgomery Street, stop working and live with Peter and write poems!’ He said, ‘Why don’t you do that?’ So, I said, ‘What happens if I get old or something?’ And he replied, ‘Oh, you’re a nice person; there’s always people who will like you’ – which really amazed me. So, in a sense he gave me permission to be free, not to worry about [the] consequences.”

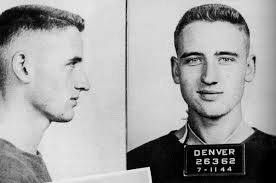

Poster for the film The Beat Generation (1959).

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ginsberg’s move to San Francisco landed him smack in the middle of the San Francisco Renaissance, a group of poets who gathered in the coffee shops and bars of that City’s North Beach. Now considered by many to be part of the Beat Generation, the San Francisco Poets preceded the Beats by at least a decade. Many of them, like Duncan, Spicer, and Robin Blaser, were openly gay at a time when Ginsberg was still struggling with his sexuality. Stan Persky, who knew Duncan, Spicer and Blaser, told John D’Emilio how these writers influenced him and other young gay men. Duncan, Spicer and Blaser, Persky said, “not only kept alive a public homosexual presence in their own work, but kept alive a tradition, teaching us about Rimbaud, Crane, and Lorca. … They carried into the contemporary culture the tradition of homosexual art and were sensitive to the work of European homosexual contemporaries. There was a conscious searching out, in fraternity, of homosexual writers. Thus, in my ‘training’ as a poet, homoerotic novels would be recommended to me. … This was at a time when the English departments of the country told us that Walt Whitman wasn’t gay. The San Francisco poets, Persky concluded, helped to create “a social milieu in which it was possible to be gay.”

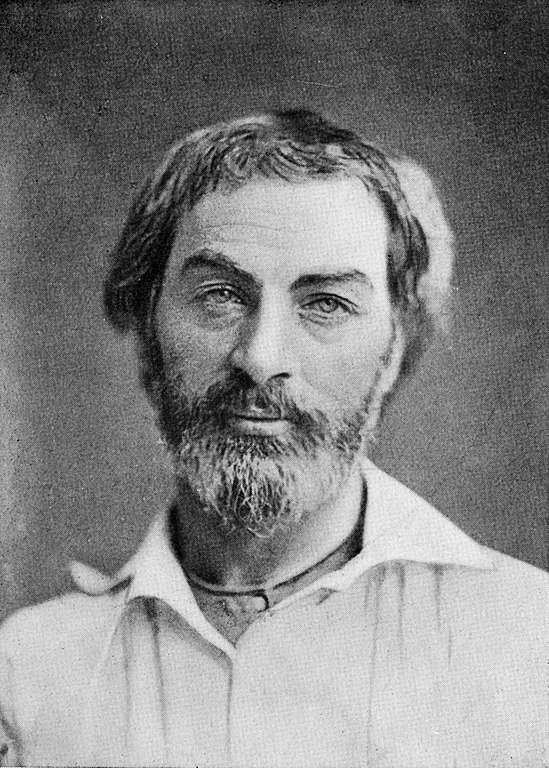

Walt Whitman Age 36, circa 1855

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Though the San Francisco poets were the first to write about their homosexuality – Duncan’s “The Homosexual in Society” was published in 1944 – it was Allen Ginsberg who made queer sex a major component of Beat literature. Part of “the homosexual tradition in American poetry” that began with Walt Whitman, Ginsberg was connected to Whitman as only men-loving men could. In his Gay Sunshine Interview Ginsberg told Allen Young that Cassady, a former lover, “slept with Gavin Arthur, who slept with Edward Carpenter, who slept with Whitman,” thus establishing a sexual link between the two poets.

In any day can be selected as the pivotal moment in the history of the Beat Generation, it was October 13, 1955, the day that Ginsberg organized a poetry reading at the Six Gallery in San Francisco. The reading was organized, Ginsberg recalled in his Journals, “to defy the system of academic poetry, official reviews, New York publishing machinery, national sobriety and generally accepted standards of good taste.” Rexroth served as master of ceremonies in a program that included readings by Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Philip Lamantia. “The crowd of over 100,” wrote Steven Watson, “included anarchists, college professors, poets, carpenters, and social leaders. Some wore fur coats, others suits and ties, others jeans and sweaters.” In the audience were Cassady, Ferlinghetti, Orlovsky and Kerouac, who collected money to buy bottles of wine that he distributed among the increasingly intoxicated (in more sense than one) audience. The evening was a success, Ginsberg recalled, and “ended with everybody absolutely radiant and happy, with talk and kissing and later big happy orgies of poets. It was an ideal evening, and I felt so proud and pleased and happy with the sense of — the sense of ‘at last a community.’”

Jack kerouac’s room in the Beat Museum, in San Francisco.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

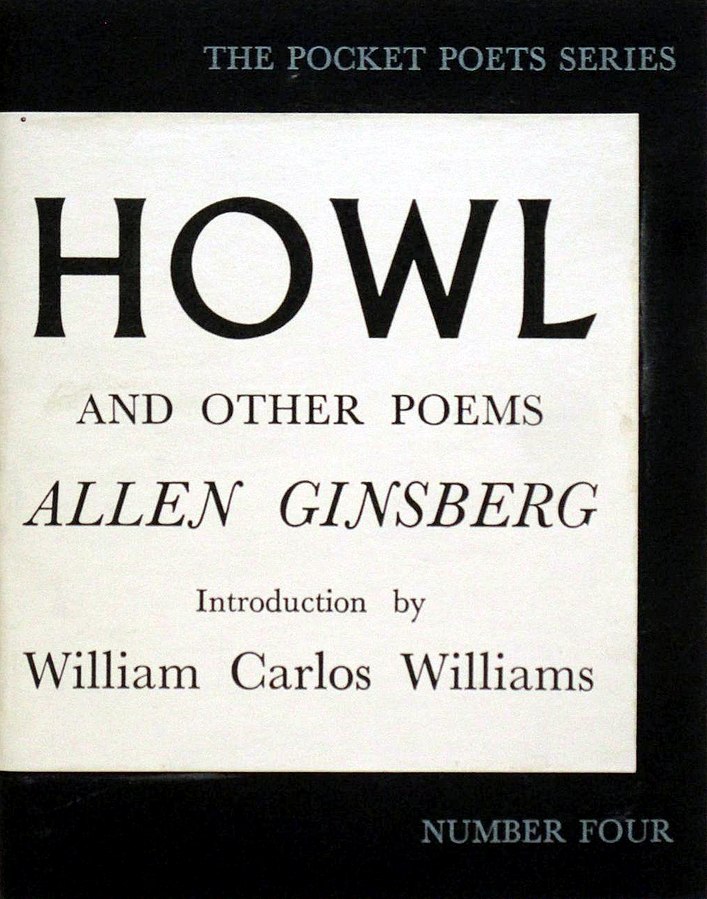

Ginsberg’s contribution to the Six Gallery reading was “a very wild, funny, tearful reading of the first part of ‘Howl.’” Accompanied by off-stage cheers from the increasingly drunk Kerouac, “Howl” was Ginsberg’s “crucial moment of breakthrough in terms of statement.” “Howl,” recalled Ginsberg, “was an acknowledgment of the basic reality of homosexual joy. That was a breakthrough in the sense of a public statement of feelings and emotions and attitudes that I would not have wanted my father or my family to see, and I even hesitated to make public. So that much was a breakthrough: literally coming out of the closet.”

The poets and artists present at the Six Gallery reading could not agree more. To McClure, “Howl” was “Allen’s metamorphosis from a quiet brilliant burning bohemian scholar, trapped by his flames and repressions, to epic vocal bard.” Rexroth called “Howl” “probably the most remarkable single poem published by a young man since the second world war.” Ferlinghetti, who recognized a masterpiece when he heard one, immediately wired an offer to publish “Howl:” “I GREET YOU AT THE BEGINNING OF A GREAT CAREER. WHEN DO I GET THE MANUSCRIPT?” Howl and Other Poems were published, in August 1956, as part of City Lights’ famous Pocket Poets series.

First-edition cover of Howl and Other Poems (1956) by the American poet Allen Ginsberg

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Unfortunately for Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti, the San Francisco poets’ enthusiastic reception for “Howl” was not shared by the public at large. To them, “Howl” was simply a dirty poem. Certainly, the poem’s celebration of “the best minds of my generation … who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy, … [and] who blew and were blown by those human seraphim, the sailors, caresses of Atlantic and Caribbean Love” contributed to the book’s censorship problems. On May 21, 1957, Captain William Hanrahan of the San Francisco Juvenile Bureau arrested Ferlinghetti and City Lights Bookstore manager Shigeyoshi Murao for selling an obscene book. As it turned out, Judge Clayton W. Horn’s decision, on October 3, 1957, that Howl and Other Poems was not obscene made it City Lights’ all-time bestseller and Ginsberg a household name.

Captain Hanrahan was not the only one to view the Beat Generation as a threat to public morals. To Bruce Bliven, writing in Harper’s, the Beats were “young hedonists who don’t really care whether something is good or evil, as long as it is enjoyable” while Herbert Gold, writing in the Nation, they were “a pack of unleashed zazous who like to describe themselves as Zen Hipsters – poets, pushers, and panhandlers, musicians, male hustlers, and a few marginal esthetes seeking new marginal directions.” But it was Bernard Wolfe who best expressed the public’s fears when he wrote that the Beat scene was “overrun with homosexuals.” The Beat Generation, wrote Ann Charters in The Portable Beat Reader, “became the spokesmen for people rejected by the mainstream, whether drug addicts, homosexuals, the emotionally dispossessed, or the mentally ill.”

More than any other work, it was Ginsberg’s “Howl” that made homosexuality, both overt and sublimated, the hallmark of the Beat Generation. Its “description of gay male sexuality as joyous, delightful, and indeed even holy turned contemporary stereotypes of homosexuality upside down,” wrote John D’Emilio in Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities. “’Howl,’ along with other poems in Ginsberg’s first collection, offered gay male readers a self-affirming image of their sexual preference. And, as the San Francisco writer most clearly identified as ‘beat,’ Ginsberg served as a bridge between a literary avant-garde tolerant of homosexuality and an emerging form of social protest indelibly stamped by the media as sexually deviant.”

More than anything else, the Beat Generation gave homosexuality legitimacy, at least in literary and intellectual circles. “[I]n a decade when homosexuality generally made its way into print through concern over national security or in stories about vice squad arrests, its discussion within the context of a major social phenomenon guaranteed a receptive, and attentive, ear among gays.” “Through the beats’ example,” concluded D’Emilio, “gays could perceive themselves as nonconformists rather than deviates, as rebels against stultifying norms rather than immature, unstable personalities.”

Jesse’s Journal

by Jesse Monteagudo