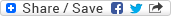

Egyptians voted on Saturday in the first free presidential election in their history to make what many find an unpalatable choice between a military man who served deposed autocrat Hosni Mubarak and an Islamist who says he is running for God.

Egyptians voted on Saturday in the first free presidential election in their history to make what many find an unpalatable choice between a military man who served deposed autocrat Hosni Mubarak and an Islamist who says he is running for God.

Reeling from a court order two days ago to dissolve a new parliament dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood, many question whether generals who pushed aside fellow officer Mubarak last year to appease the pro-democracy protests of the Arab Spring will honor a vow to relinquish power by July 1 to whoever wins.

“Both are useless but we must choose one of them unfortunately,” said Hassan el-Shafie, 33, in Mansoura, north of Cairo, exasperated like many who picked centrists in last month’s first round and now face a choice between two extremes.

With neither a parliament nor a new constitution in place to define the president’s powers, the outcome from Saturday and Sunday’s run-off will still leave 82 million Egyptians, foreign investors and allies in the United States and Europe unsure about what kind of state the most populous Arab nation will be.

Both contenders may herald further turbulence. An Islamist president will face a mistrustful army, while a victory by a Mubarak-era general will rile the revolutionaries on the street.

There are no reliable opinion polls for guidance, but former air force commander Ahmed Shafik, 70, Mubarak’s prime minister in the last days of his rule, surged from outsider status and into the run-off. He has kept up the momentum by playing on fears about rule by an Islamist and the chaos that might bring.

His rival, the Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsy, paints himself as the last revolutionary in the race. He can be sure of solid support from the group’s network of disciplined supporters built up over decades. But he has struggled to broaden his appeal.

A result may emerge within hours of polls closing on Sunday. Turnout in the first round last month was only 46 percent. An election official said Saturday’s voting had been steady.

For the urban youth who drove the anti-Mubarak revolt, the decision is agonizing, so much so that some of the 50 million voters will spurn both, despite the blood spilt on the streets to end a 30-year rule marked by rigged and meaningless ballots.

Among those staying away was the sister of Khaled Said, a young activist whose death in police custody in 2010 became a cause célèbre which helped ignite the popular uprising: “I am boycotting this sham election,” Zahra Said told Reuters.

“What guarantees does Shafik offer that he will not jail or torture youths? During his premiership many youths died and he did nothing,” she said in her home city of Alexandria.

“Morsy is no good because he has manipulated the revolution, at times backing the youth and at other times abandoning them.”

Yet, whoever wins, the army retains the upper hand. A Shafik presidency means a man steeped in military tradition will be back in charge, just like every president since the end of the monarchy in 1953. If Morsy wins, soldiers can still influence how much authority he has in the yet-to-be-written constitution.

MOOD CHANGE

Many fear the Brotherhood will not accept a defeat quietly and a Shafik win could touch off new unrest on the streets, forcing the army to take sides to impose order and further unsettle a heavyweight state at the heart of a troubled region.

It is a dramatic mood change from the euphoria when Mubarak fell on February 11, 2011. Many are now exhausted and frustrated after a messy and often violent interim period in which the generals have promised to set Egypt on a democratic path.

“If we elect Shafik, I think we can say the Egyptian revolution is over,” said Ali Mahmoud Ibrahim, 44, heading to the polls in Cairo. “I will give Morsy a chance to make Egypt a good, Islamic state and to implement Islamic sharia law.”

Yet, Shafik has gained traction among those who see him having the army’s backing to restore order and revive an economy teetering on the brink of crisis with its foreign reserves drained sharply after tourists and investors packed up.

“He has exactly what we need in a leader. A strong military man to have a strong grip on the state and bring back security,” said Hamdy Saif, 22, a student in Cairo’s Nasser City district.

There are signs of exasperation with the Brotherhood’s push for power after a revolt driven initially by the secular, urban middle class. The Brotherhood secured the biggest bloc in parliament after running for more seats than it said it would. It then reneged on its pledge not to run for president.

The court ruling to dissolve parliament reverses its gains, though that move has helped the group win some sympathizers.

“I was going to vote for Shafik but after parliament was dissolved, I changed my mind and will vote Morsy. There is no more fear of the Islamists dominating everything,” said Ahmed Attiya, 35, an IT technician in Cairo’s Zamalek district.

Critics denounced the court’s parliament ruling as a “soft coup” and compared it to the start of Algeria’s civil war, when the army cancelled an election won by Islamists 20 years ago.

But the Brotherhood renounced violence as a means to achieve political change in Egypt decades ago and an Islamist uprising in the 1990s was crushed by Mubarak and the same security forces which have survived last year’s revolt intact.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces of about 20 generals is led by Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi, who was Mubarak’s defense minister for two decades. The army controls businesses ranging from real estate to consumer goods factories.

Tantawi sent a letter to parliament ordering it to disperse and barring members from returning to the building, an official in the speaker’s office said. The Brotherhood said the council wanted to “take all powers, despite the will of the people”.

‘DANGEROUS DAYS’

Hardline Islamist violence this month in Tunis, where the first Arab Spring uprising inspired Egyptians, has hardened fears of political Islam, notably among tourism workers, secular activists, women and Christians, who are a tenth of Egyptians.

“With Shafik I know what policy he is going to pursue but Morsy is enigmatic and shadowy like their underground group,” said Walid Farouk, a 42-year-old cook, referring to the Brotherhood which was banned for decades under Mubarak.

But some threaten action after a Shafik victory that would disappoint many who massed on Cairo’s Tahrir Square last year.

“If Shafik wins, I will be the first one to gather the people and go to Tahrir Square,” said Sherif Abdel Aziz, 25, in Fayoum, a city south of Cairo.

The Brotherhood has warned of “dangerous days” and said a Shafik win could wipe out the gains of the revolt. It listed poll violations, including conscripts voting although they are barred. Election officials said any such violators were stopped.

Reflecting its suspicions, one Brotherhood official said many of the group’s supporters would vote on Sunday to avoid any tampering with ballot boxes overnight.

International monitors gave guarded approval of the first round vote last month and Egyptian groups listed a range of mostly only minor violations on Saturday.

Both candidates have sought the centre ground, promising to rule in the spirit of the revolution: “It is not correct that the military council wants to rule through me,” said Shafik, seen as a potential successor even in Mubarak’s time although he and other contenders were overshadowed by the president’s son.

Protesters chanted slogans for and against Shafik as he voted in Cairo. But he did not face a hail of shoes or the kind of abuse he received when he voted in the first round.

Morsy has played down talk of a crackdown on beachwear and alcohol that would hurt tourism and steered away from confrontation with Israel after three decades of cool peace maintained during Mubarak’s military-backed rule.

Mobbed by backers after voting in Zagazig in the Nile Delta, Morsy said: “There is absolutely no room for Mubarak’s aides.”

But both candidates are defined by those who promoted them. Morsy says he is running because God expects him to offer his sacrifice for the nation. Shafik’s air force career shadowed that of Mubarak, his elder by 13 years.

CAIRO (Reuters) – (By Yasmine Saleh and Marwa Awad; Additional reporting by Samia Nakhoul in Cairo, Tom Perry in Fayoum and Tamim Elyan in the Nile Delta; Writing by Edmund Blair and Alastair Macdonald; Editing by Samia Nakhoul)